Of Mice and Milkweed

Story by, Dr Kenneth Liegner. Published in Natural History Magazine, November 2025

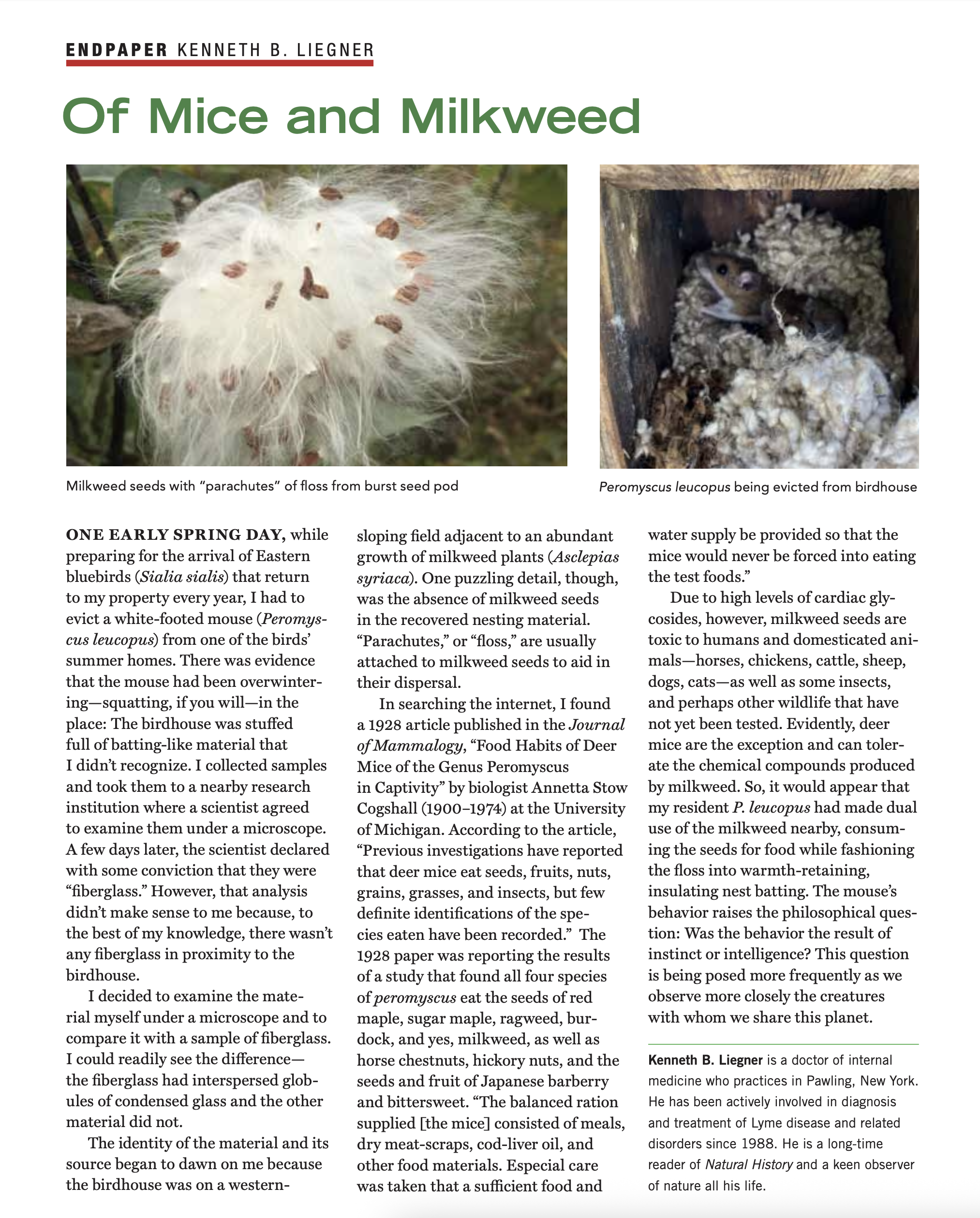

Of Mice and Milkweed One early spring day, while preparing for the arrival of Eastern bluebirds (Sialia sialis) that return to my property every year, I had to evict a white-footed mouse (Peromys- cus leucopus) from one of the birds’ summer homes. There was evidence that the mouse had been overwinter- ing—squatting, if you will—in the place: The birdhouse was stuffed full of batting-like material that I didn’t recognize. I collected samples and took them to a nearby research institution where a scientist agreed to examine them under a microscope. A few days later, the scientist declared with some conviction that they were “fiberglass.” However, that analysis didn’t make sense to me because, to the best of my knowledge, there wasn’t any fiberglass in proximity to the birdhouse.

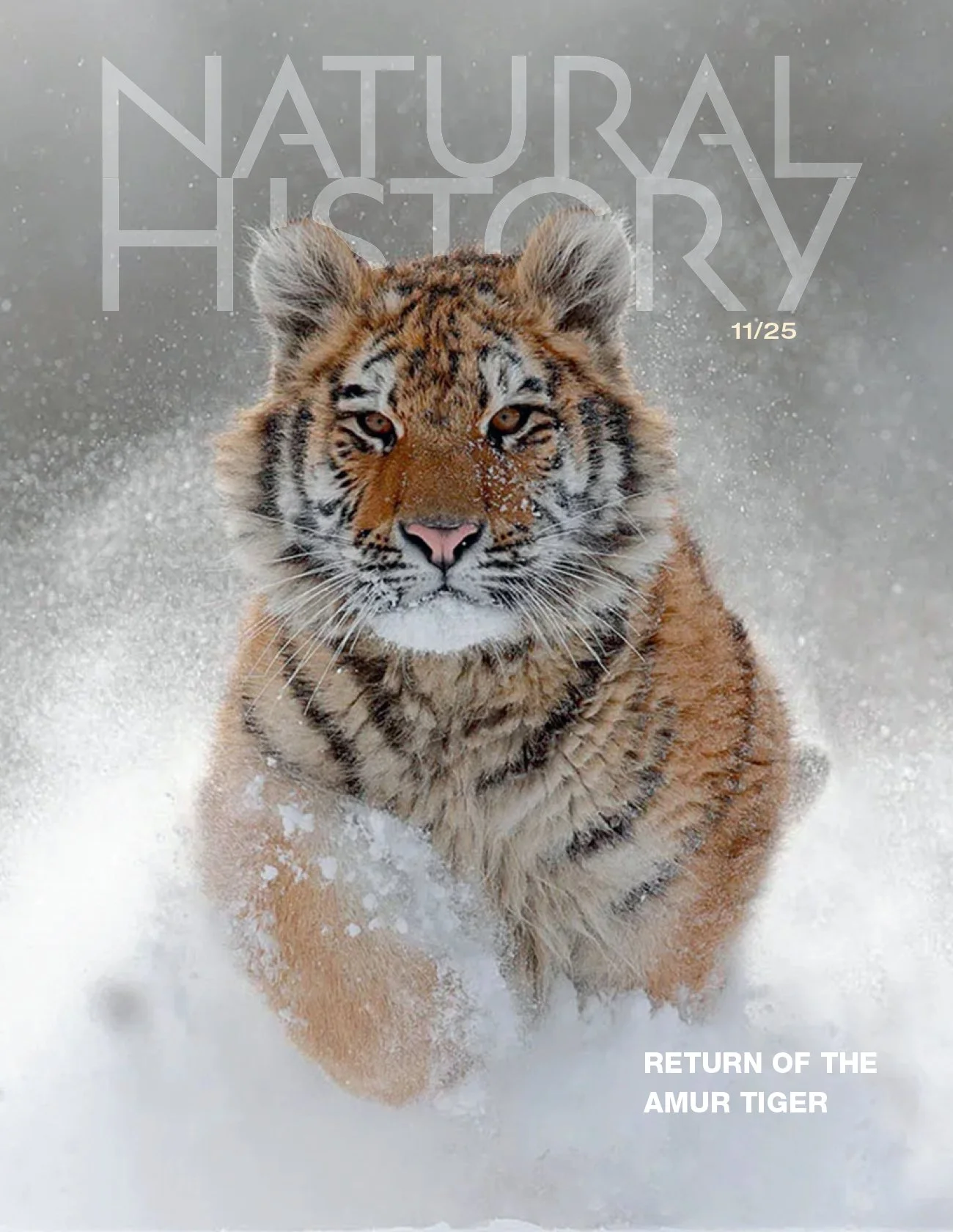

I decided to examine the mate- rial myself under a microscope and to compare it with a sample of fiberglass. I could readily see the difference— the fiberglass had interspersed glob- ules of condensed glass and the other material did not. The identity of the material and its source began to dawn on me because the birdhouse was on a western- sloping field adjacent to an abundant growth of milkweed plants (Asclepias syriaca). One puzzling detail, though, was the absence of milkweed seeds in the recovered nesting material. “Parachutes,” or “floss,” are usually attached to milkweed seeds to aid in their dispersal.

NATURAL HISTORY

Photography by Jonathan C. Slaght

In searching the internet, I found a 1928 article published in the Journal of Mammalogy, “Food Habits of Deer Mice of the Genus Peromyscus in Captivity” by biologist Annetta Stow Cogshall (1900–1974) at the University of Michigan. According to the article, “Previous investigations have reported that deer mice eat seeds, fruits, nuts, grains, grasses, and insects, but few definite identifications of the spe- cies eaten have been recorded.” The 1928 paper was reporting the results of a study that found all four species of peromyscus eat the seeds of red maple, sugar maple, ragweed, bur- dock, and yes, milkweed, as well as horse chestnuts, hickory nuts, and the seeds and fruit of Japanese barberry and bittersweet. “The balanced ration supplied [the mice] consisted of meals, dry meat-scraps, cod-liver oil, and other food materials. Especial care was taken that a sufficient food and water supply be provided so that the mice would never be forced into eating the test foods.”

Due to high levels of cardiac glycosides, however, milkweed seeds are toxic to humans and domesticated animals—horses, chickens, cattle, sheep, dogs, cats—as well as some insects, and perhaps other wildlife that have not yet been tested. Evidently, deer mice are the exception and can tolerate the chemical compounds produced by milkweed.

So, it would appear that my resident P. leucopus had made dual use of the milkweed nearby, consum- ing the seeds for food while fashioning the floss into warmth-retaining, insulating nest batting. The mouse’s behavior raises the philosophical ques- tion: Was the behavior the result of instinct or intelligence? This question is being posed more frequently as we observe more closely the creatures with whom we share this planet.

Kenneth B. Liegner is a doctor of internal medicine.

He has been actively involved in diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease and related disorders since 1988. He is a long-time reader of Natural History and a keen observer of nature all his life.